It seems that the electric car market is only going to expand. But what about the mainstay of VACC members - the internal combustion engine? There are currently about a billion cars in the world and virtually all of them are powered by internal combustion engines (ICE).

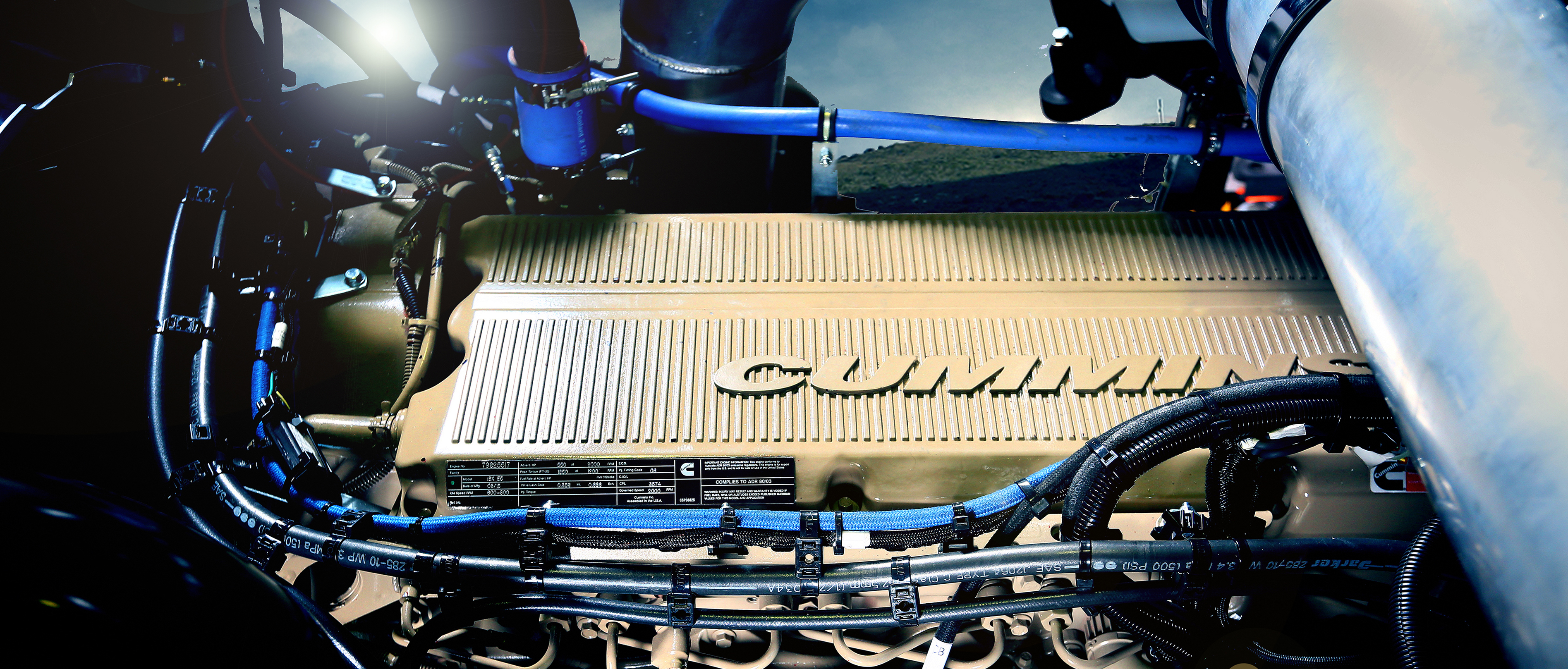

Although electrification of the world’s vehicle fleet will continue – and very quickly given some predictions that seem quite reasonable – the internal combustion engine is not going away any time soon. In some applications, like heavy road transport, some mobile plant engines and the like, it can’t.

Battery powered plant just isn’t up to the job at the moment. So, the factories churning out internal combustion engines around the world are likely to continue production in the near term and perhaps the longer term, too.

Of course, one of the main problems with internal combustion engines is emissions. This is particularly so with diesel engines, which power virtually the whole heavy road transport industry, and more besides.

Virtually anything that burns fuel is subject to an emissions regulation. Those with which we’re most familiar are the Euro Standards for vehicles. We’re now at Euro 6 for petrol and diesel engines, but it’s still not enough.

Emissions standards generally call to mind things like carbon monoxide (CO), oxides of nitrogen (NOx) and hydrocarbons (HC). The Euro standards have had, or are having, the desired effect of reducing these emissions. Also, particulate matter (PM) has always been part of the Euro Emission Standards.

However, as the awareness of health hazards associated with extremely fine particles grows, these are gaining greater prominence in the minds of regulators. And, of course, CO2 from fossil fuels has also become a major concern across the globe for obvious reasons.

Diesel particulates and the filters that are supposed to contain them have become a major consideration. Awareness of them has increased because of health studies, but also simply because of the cost of replacing them.

Anyone who’s had to pay to do so will forever remember the cost shock of the job. And unfortunate owners have discovered many things that can render a filter inoperative necessitating replacement. Some owners have simply removed them but this has been revealed to be an incredibly bad idea.

The nomenclature of particulate matter s defined by the size of the particles in microns. A micron is a thousandth of a millimetre or a millionth of a metre. So, PM10 particles are 10 microns or less in diameter. For reference, the average cross section of a hair is about 70 microns.

PM10 particles en masse are the ones you used to see belching out of diesel exhausts as black smoke. In the main, they are particles of carbon and sulfur. The Euro Standards have had the desired effect and diesel exhausts don’t look like that anymore.

PM2.5 particles are 2.5 microns across and generally referred to as fine particles. PM10 particles tend to interact most with the mouth and throat but coughing, sneezing and swallowing tend to get rid of them. PM2.5 particles reach the lungs and are highly detrimental to health, but they are supposed to be controlled by particulate filters. There are also PM1.0 particles, which are designated as ultrafine particles. But it gets worse.

Diesel engines also produce PM0.1 particles which have cross-sections of just 0.1 microns, or 100 nanometres. They are referred to as nanoparticles. They get into the blood via the lungs and their effects on human health are horrendous.

Studies are showing that health issues caused by nanoparticles are responsible for an enormous portion of the health costs we bear as a society. It has to stop.

Diesel engines are heavy emitters of particulates because of the way they work. As fuel is sprayed into the extremely hot compressed air in the combustion chamber it forms virtually the full range of A/F ratios as it spreads into the flame cloud.

Conventional port injection petrol engines don’t do this because the fuel is introduced to the air in the port behind the inlet valve. Consequently, it enters the chamber as a homogenous mixture.

Now, of course, we have direct injection petrol engines. These offer a number of advantages but, like diesels, they also suffer from broad A/F ratios across the chamber. This is most unfortunate and studies are starting to show that direct petrol injection engines also contribute to urban health problems.

Read Is there a future for the internal combustion engine (Part 2). Alternatively, view the full article and accompanying imagery in the October 2019 issue of Australian Automotive (page 32).